Originally published in The American Prospect on March 18th, 2016.

—–

It was not so long ago that Charlotte, North Carolina, was widely considered “the city that made desegregation work.” The Queen City first pioneered busing to desegregate schools in 1969, and when the Supreme Court upheld that strategy as a legal remedy for school segregation two years later in its landmark Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education ruling, districts across the South began busing students as well.

In the past 15 years, however, Charlotte has seen a rapid resurgence in segregated schooling. Following a late 1990s decision that said court-mandated integration was no longer necessary, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) grew quickly divided by race and class, and the economic isolation continues to intensify with each passing year. Though CMS is still considered a relatively high-performing school system, a closer look at the data reveals deeply unequal outcomes among the district’s 164 schools.

For more than a decade, local residents ignored the demographic shifts taking place within CMS. Political leaders, as well, seemed to just have no energy left to expend on school diversity following their highly publicized school segregation lawsuits. Yet now, due to a district policy that requires school board members to revisit student assignments every six years, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg community finds itself facing a rather unusual opportunity. Wary of litigation, but troubled by the damning diversity data, Charlotte leaders have been working cautiously over the past year to see if there might be any popular support for breaking up pockets of poverty within CMS.

Their timing may be just right. In addition to sobering statistics on school segregation in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, new research out of Harvard University and the University of California at Berkeley found that Charlotte ranks dead last in the nation in terms of upward mobility, and that racial segregation and school quality are two main culprits behind this. Moreover, after years of lackluster results from other school turnaround efforts, resistance to shuffling students as a way to improve school quality is softening.

The political momentum in favor of school segregation in Charlotte is fairly new, but so is the backlash against it. Charlotte-Mecklenburg has seen a 15-year population surge, predominately in the county’s northern and southern regions. Many of the county’s newcomers missed Charlotte’s desegregation history, and see no real reason to bring it back. They moved into their communities, they say, largely for the schools. As more leaders explore how CMS might revamp student assignment, a growing number of parents have begun to raise objections—warning officials that they would not hesitate to send their children to private schools, or to the state’s notably segregated charter sector, if they had to.

Last summer, when it became clear that the CMS school board was thinking of revisiting student assignment, a group of pro-integration community members began organizing in support of the idea. And so back in July, OneMeck was born—a grassroots coalition of residents committed to making Charlotte-Mecklenburg a place where diverse individuals live, work, and attend school together. Through public forums, social media, and one-on-one conversations, OneMeck advocates began to make their case.

“We spent a few months figuring out what we were for and how we would structure ourselves, and we’re still evolving even now,” says Carol Sawyer, a co-founder of OneMeck. “But we have no intention of becoming a 501c(3); we really value our nimbleness and our ability to advocate as a community organization.”

Students also got involved. Through the organization Students for Education Reform, (SFER), CMS students began to strategize how they could best interject their personal experiences into an increasingly heated public debate over school segregation.

“Even though school board members said they wanted to hear from students, they weren’t actually invited to the table in any of these conversations,” says Kayla Romero, a former CMS teacher and current North Carolina SFER program coordinator. “This issue is going to directly impact students, they are the ones currently in the system, but people were not seeking their opinions out or intentionally bringing them to the table.”

OneMeck supporters say they are not advocating for any one specific policy, and that they believe there are a number of steps CMS could take to reduce racial and economic segregation. They are encouraging the school board to hire a national consultant who could come in and study the school district, and make recommendations on how to best legally, and strategically, diversify CMS schools.

Throughout the summer and fall of 2015, the public discussion in Charlotte revolved largely around issues of race and desegregation. But beginning in 2016, suburban families started to ramp up their efforts to shift the narrative. In February, hundreds of parents joined two new groups—CMS Families United for Neighborhood Schools and CMS Families for Close to Home Schools and Magnet Expansion—which sought to reframe the conversation around the importance of neighborhood schools, and to express collective opposition to what they called “forced busing.” Some even began to sell T-shirts that read “#Close-To-Home-Schools #NOforcedbusing.”

Christiane Gibbons, a co-founder of the CMS Families United For Neighborhood Schools, (now renamed CMS Families for Public Education) says when she first learned that the school board was rethinking student assignments in early February, she felt compelled to alert local parents to the dangers of forced busing. I asked her if forced busing was on the table at this time. “Who knows?” she responded. “But it seemed like, for a lot of people, an option for alleviating pockets of poverty is to bus in and bus out.”

Advocates of diverse schools point out that CMS actually buses students more now than the district ever did at the height of desegregation. The CMS school board chairperson, Mary McCray, has also stressed that student assignments would be based on choice, and not on forced busing. Since 20,000 students already attend magnet schools throughout the district, integration advocates say figuring out how to improve and expand those models is one choice-based option CMS could consider.

“In some high-wealth suburban neighborhoods there’s been claims that OneMeck is pushing ‘forced busing,’ but that’s been sort of dog whistle politics,” says Sawyer. “We’ve never said anything like that, and neither has any board members. It’s a pure fabrication.”

Whatever the case, many parents began pressing the school board and other local political leaders to commit to “home school guarantees”—promises that no matter what else changes with student assignment, children could still attend the neighborhood schools that their parents have expected them to enroll in. In three towns north of Charlotte—Huntersville, Cornelius, and Davidson—political leaders passed resolutions affirming that they want every student guaranteed a spot within their neighborhood school. In two towns south of Charlotte—Matthews and Mint Hill—the mayors even floated the idea of splitting off from CMS if the school board goes forward with revamping student assignments.

“That’s not a realistic threat,” says Sawyer. “Though it makes good copy.”

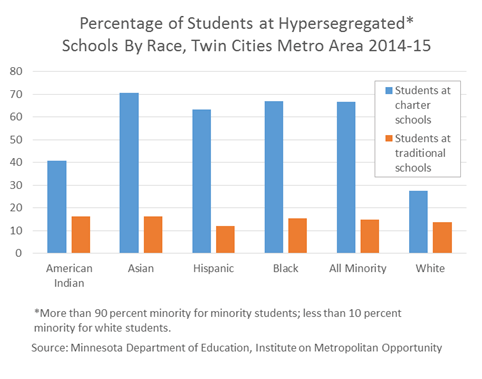

Aside from discussions that smaller suburban towns may secede from the district, leaders take far more seriously the threat that parents may send their children to private schools or charter schools if their traditional public schools no longer seem desirable. Last year, researchers at Duke University published a study suggesting that white parents in North Carolina were already using charters as a way to avoid racially integrated public schools.

On the nine-person CMS school board, Rhonda Lennon, who represents northern Mecklenburg County, has been the fiercest critic of redrawing lines; for months she has emphasized that families would certainly leave CMS if the board interferes with student assignment, and that she might open her own charter school, if parents in her community lost their home school guarantee.

“I think it’s a valid fear that parents have; I don’t think this is ‘chicken little’,” says Amy Hawn Nelson, an educational researcher at UNC Charlotte. “When you look at the aggregate school level performance data in some high poverty racially segregated schools, it can look frightening. Every parent wants the best school for their child, and for parents that have a choice, they are going to choose a school that is high-performing.”

At the end of January, the school board released an online survey inviting parents, CMS staff members, and other Mecklenburg County residents to share their thoughts and opinions on student assignments. Board members said they would use the results—which were published in a 241-page report—to guide their decisions. The online survey, which ran from January 29 until February 22, garnered more than 27,000 responses.

In addition to the survey, the CMS school board voted in late February on a set of six goals to consider when re-evaluating student assignment. These included providing choice and equitable access to “varied and viable” programmatic options; maximizing efficiency in the use of school facilities, transportation, and other resources to reduce overcrowding; and reducing the number of schools with high concentrations of poor and high-needs children.

CMS has since put out a request for a proposal for a national consultant to help the district develop a plan. The consultant would consider, among other things, the board’s approved goals and the results of the countywide survey. CMS plans to make a hire sometime this month.

Some parents say the board is getting this all wrong, and that focusing on student assignments is a distraction from the district’s real problems. “What’s really disheartening about all this is that people are making it about ‘us versus them’ and about race and desegregation, but it’s not,” says Gibbons. She thinks there should be greater focus on improving individual schools, through strategies like increasing parent involvement and expanding after school programming. Gibbons says she does not see changing student demographics as a way to improve schools.

At the start of the 2012-2013 school year, CMS, along with local philanthropic and business communities in Charlotte launched Project LIFT—a five-year public-private partnership to boost academic achievement. The program selected nine low-performing Charlotte schools and infused them with an additional $55 million in private investment. Three years into the experiment, however, researchers have found only modest and mixed evidence of academic improvement.

“I think Project LIFT is a school reform effort to make segregation work, and it hasn’t,” says Sawyer, of OneMeck.

Gibbons disagrees. “I think it’s a great turnaround program, I think it’s obviously beneficial,” she says. “It was the first time they did it so it may need tweaks, I don’t know enough about the actual numbers, but I think those types of turnaround programs are what is going to really benefit the under-performing schools.”

Some of the SFER students that Kayla Romero works with attend Project LIFT schools. “When people say ‘oh we just need more money,’ it’s been helpful to use Project LIFT as an example,” she says. Though spending more money has undoubtedly helped in some ways—such as providing students with better technology, and enabling administrators to employ more strategic staffing—Romero says students recognize that it hasn’t been enough.

The disagreements taking place in Charlotte mirror those playing out in districts all over the country. How much does money matter? Can segregated schools be equal? How should we factor in school choice? How should we define diversity?

Proponents of desegregating Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools point to a significant body of research that says diverse schools provide better social and academic education for all children. OneMeck launched the #DiversityWorks campaign, where organizers asked CMS residents to submit videos explaining how they have benefited from attending diverse schools. They also point to research on economic opportunity that came out of Harvard and Berkeley last year, which found Mecklenburg County is the worst big county for escaping poverty after Baltimore; in 2013 the researchers ranked Charlotte as 50th out of 50 big cities for economic mobility.

Still, some CMS residents balk at OneMeck’s fervent advocacy. In a Charlotte Observer op-ed, Jeremy Stephenson, who previously ran for school board, protested that those who push to use student assignment to break up concentrations of poverty “accept as gospel” that this will raise the achievement of all students. “They accept this diversity panacea as both empirical truth and an article of faith,” he writes, alleging that academia is “merging into advocacy” as it did with tobacco-funded cancer research. Stephenson argued that panel discussions “feature no diversity of thought; support for neighborhood schools is cast as xenophobic; and so postured, any questioning is heretical.”

Despite Charlotte-Mecklenburg’s historical legacy of school desegregation, hardly anyone describes that history as central to the conversations taking place today. Sandra Conway, an education consultant who has been working in conjunction with OneMeck, says she and her allies hope to mobilize Charlotte-Mecklenburg around a new, shared commitment to diverse schools.

“We’ve just really been trying to get people together to think about what kind of city we want to be,” says Conway. “We’ve grown so dramatically, we’re a Technicolor city, we’re a Southern city, and race is at play. But we need to have a new vision going forward, and if you don’t understand your history, and you don’t understand the data—that’s a problem. So we’ve just been working hard for over a year to get that out there.”

James Ford, awarded the 2014-2015 North Carolina Teacher of the Year, was a black CMS graduate during desegregation. As an educator today, Ford has been sharing his story to help raise support for reviewing student assignment. “As America becomes more brown, the question is not just whether or not we want integrated schools, but do we want to live in an integrated society? Are we an inclusive or exclusive community?” he wrote in Charlotte Magazine. “The answer depends on how we see ourselves.”

“I think for many kids growing up in Charlotte, segregation has just been the norm,” says Romero. “Some of them could live in this city for their whole lives and never come across white kids. However, some of their parents have had those experiences and do speak out about being part of the integration movement and the opportunities it created for them.”

The school board plans to continue reviewing student assignments throughout most of 2016, and any approved changes it makes would take effect no sooner than the 2017-2018 school year.

Tensions are high, but some school diversity advocates predict that the political landscape will calm down if and when a consultant presents the community with a real plan. “In the absence of a plan, you’ll have all sorts of fear mongering,” one activist confided. “It doesn’t matter how much we say that’s not the case, that there won’t be forced busing—until a plan is presented, people will continue to freak out.”

Even opponents of reassigning students have acknowledged that some of the current CMS boundaries are a bit peculiarly drawn. An article published in The Charlotte Agenda looked at various “gerrymandered” maps and found that it would be relatively easy to increase student diversity in schools without resorting to miles and miles of extra busing. Gibbons acknowledged “there are definitely some lines that don’t make sense” on the maps.

“OneMeck is feeling pretty energized,” says Sawyer. “We realize that we are facing tremendous fear, but we’re trying to show that we can make all our schools better for all our kids.”