Originally published in the Spring 2016 print issue of The American Prospect

—–

In 2013, citing a $1.4 billion deficit, Philadelphia’s state-run school commission voted to close 23 schools—nearly 10 percent of the city’s stock. The decision came after a three-hour meeting at district headquarters, where 500 community members protested outside and 19 were arrested for trying to block district officials from casting their votes. Amid the fiscal pressure from state budget cuts, declining student enrollment, charter-school growth, and federal incentives to shut down low-performing schools, the district assured the public that closures would help put the city back on track toward financial stability.

One of the shuttered schools was Edward Bok Technical High School, a towering eight-story building in South Philadelphia spanning 340,000 square feet, the horizontal length of nearly six football fields. Operating since 1938, Bok was one of the only schools to be entirely financed and constructed by the Public Works Administration. Students would graduate from the historic school with practical skills like carpentry, bricklaying, tailoring, hairdressing, plumbing, and as the decades went on, modern technology. And graduate they did—at the time of closure, Bok boasted a 30 percent–higher graduation rate than South Philadelphia High School, the nearby public school that had to absorb hundreds of Bok’s students.

The Bok building was assessed at $17.8 million, yet city officials sold it for just $2.1 million to Lindsey Scannapieco, the daughter of a local high-rise developer. On their website, BuildingBok.com, Scannapieco and her team envision repurposing the large Bok facility into “a new and innovative center for Philadelphia creatives and non-profits.” They describe the “unprecedented concentration of space” in the Bok building for “Do-It-Yourself innovators, artists, and entrepreneurs” to congregate.

In August 2015, Scannapieco launched Bok’s newest debut, a pop-up restaurant on the building’s eighth floor, which served French food, craft beers, and fine wines. The rooftop terrace was decorated with student chairs and other school-related items found inside the building. Young millennials dubbed the restaurant “Philly’s hottest new rooftop bar,” while longtime residents and educators called it “a sick joke.” Situated in a quickly gentrifying community where nearly 40 percent of families still have incomes of less than $35,000, there was little question about who would be sipping champagne and munching on steak tartare on Bok’s top floor.

When it comes to closing schools, Philadelphia is not alone. In urban districts across the United States—from Detroit to Newark to Oakland—communities are experiencing waves of controversial school closures as cash-strapped districts reckon with pinched budgets and changing politics.

The Chicago Board of Education voted to close 49 elementary schools in 2013—the largest mass school closing in American history. The board assured the distressed community that not only would the district save hundreds of millions of dollars, but students would also receive an improved and more efficient public education.

Yet three years later, Chicago residents are still reeling from the devastating closures—a policy decision that has not only failed to bring about notable academic gains, but has also destabilized communities, crippled small businesses, and weakened local property values. With the city struggling to sell or repurpose most of the closed schools, dozens of large buildings remain vacant, becoming targets of crime and vandalism throughout poor neighborhoods. “These schools went from being community anchors into actual dangerous spaces,” says Pauline Lipman, an education policy professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

African Americans have been hit hardest by the school closings in Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere. While black students were 40 percent of Chicago’s school district population in 2013, they made up 88 percent of those affected by the closures. In Philadelphia, black students made up 58 percent of the district, but 81 percent of those affected by closures. Closure proponents insist that shutting down schools and consolidating resources, though certainly upsetting, will ultimately enable districts to provide better and more equitable education. It’s easier to get more money into the classroom, the thinking goes, if unnecessary expenses can be eliminated. But many residents see that school closures have failed to yield significant cost savings. They also view closures as discriminatory—yet another chapter in the long history of harmful experiments deployed by governments on communities of color that strip them of their livelihood and dearest institutions.

Today “the pain is still so raw, it’s not business as usual,” Reverend Robert Jones told me, speaking inside the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, the oldest black grassroots center in Chicago. Indeed, threats of further closures have not abated since 2013. Jones was one of 12 local residents to go on a highly publicized hunger strike late last summer, starving himself for 34 days to prevent another beloved school from being shut down. Their dangerous efforts proved successful; the district reversed its decision and pledged to reopen Walter H. Dyett High School, located on the South Side of Chicago.

Rather than shutter schools, residents argue, districts should reinvest in them.

Rather than shutter schools, residents argue, districts should reinvest in them.They point to full-service community schools, a reform model that combines rigorous academics with wraparound services for children and families, as promising alternatives. The effort to fight back against school closures has grown more pronounced in recent years, as tens of thousands across the country begin to mobilize through legal and political channels to reclaim their neighborhood public schools.

TO TALK ABOUT SCHOOL CLOSURES, one must talk about school buildings. The average age of a U.S. public school facility is nearly 50 years old, and most require extensive rehab, repair, and renovation—particularly in cities. None of the school buildings constructed before World War II were designed for modern cooling and heating systems, and many schools built to educate baby boomers in the 1960s and 1970s were constructed hurriedly on the cheap. Studies find that poor and minority students attend the most dilapidated schools today.

But the federal government offers virtually no economic assistance to states and local districts trying to shoulder the costs of building repairs. And things don’t look much better on the state level, either. Jeff Vincent, the deputy director of the Center for Cities & Schools at University of California, Berkeley, says that state spending has failed to keep up with the needs in schools following the recession, leaving local districts to take on those capital costs even if they can’t afford to.

Despite contributing next to nothing toward school facility spending, the federal government encourages public-school closure and consolidation as a strategy to boost academic performance. Such school improvement interventions for “failing” schools began during the controversial No Child Left Behind era, but financial incentives to close schools and open charters really ramped up under the Obama administration.

“Our communities have been so demonized to the point that nobody thinks they’re good. But no, our institutions have been sabotaged,” says Jitu Brown, the executive director of Journey For Justice (J4J), an alliance formed in 2013 that connects grassroots youth and parents fighting back against school closures. “These districts—Newark, Chicago, Detroit—they all cry ‘broke’ as they shift major portions of their budget towards privatization while neglecting and starving neighborhood schools.”

Besides pointing to low performance, districts often justify closing schools on the basis of the facilities being “underutilized.” This refers to buildings deemed too large for the number of students enrolled, and thus too expensive for districts to operate. Critics of school closures say that how districts determine “utilization” insufficiently accounts for the variety of ways communities use and rely on school facilities. Moreover, Mary Filardo, executive director of the 21st Century School Fund, says that urban districts tend to “completely underestimate” how much space is needed for special education and early childhood learning.

“When you’re resource-starved, you tend to take a defensive approach,” says Ariel Bierbaum, a Ph.D. student in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. “You’re in a crisis mode, you’re looking to balance your books, so you’re not necessarily thinking the most creatively” about how to use some of the seemingly excess facility space.

PUBLIC SCHOOLS HAVE ALWAYS impacted communities in ways that go beyond just educating young people. Well-maintained school facilities can help revitalize struggling neighborhoods, just as decrepit buildings can hurt them. And whether it’s attracting businesses and workers into the area, directly affecting local property values, or just generally enhancing neighborhood vitality by creating centralized spaces for civic life, research has long demonstrated the influential role schools play within communities.

Yet most existing research on school closures has failed to explore the ways in which shuttering schools impacts these civic spheres; instead researchers have adopted a narrower focus on how school closures impact school district budgets and student academic achievement. On both of these fronts, though, the record has not been impressive.

Researchers find that what districts promise to students, staff, and taxpayers when preparing to close schools differs considerably from what actually happens when they close. For example, most students who went to schools that were closed down in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Newark—whether for fiscal reasons or for low academic performance—were transferred to schools that were not much better, and in some cases even worse, than the ones they left. In Chicago, for example, 87.5 percent of students affected by closures did not move to significantly higher-performing schools. Children also frequently encounter bullying and violence at their new schools, while teachers are often unprepared to handle the influx of new students.

Moving students around can negatively impact student achievement, and closures exacerbate such mobility. In some cities, students have been bumped around two, three, four times—as their new schools were eventually slated for closure, too.

Not all research casts school closures in a uniformly negative light. One study found that New York City school closures had little impact—positive or negative—on students’ academic performance at the time the schools were shut down, yet “future students”—meaning those who had been on track to attend those schools before they closed—demonstrated “meaningful benefits” from attending new schools. Another study found that while most children experienced negative effects on their academic achievement during the year they transitioned to new schools, such negative effects were impermanent, and student performance rebounded to similar rates as their unaffected peers the following year. Essentially, researchers find that there can be substantial positive effects if students are sent to much better schools than they ones they left; however, the reality is that most students do not go to such schools.

In addition to overselling academic gains, districts also tend to overstate how much money they’ll save from shutting down schools. When Washington, D.C., closed down 23 schools in 2008, the district reported it would cost them $9.7 million. A 2012 audit found the price was actually nearly $40 million after taking into account the cost of demolishing buildings, transporting students, and the lost value of the buildings, among other factors. Another study conducted by the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2011 found that cost savings are generally limited, at least in the short term, and such savings come largely through mass employee layoffs.

Bierbaum, however, has been studying Philadelphia’s school closures from a broader community-development and urban-planning perspective to understand how school closures, sales, and reuses are related to larger issues of metropolitan-wide racial and class inequality. This means examining school closures in the context of neighborhood change, like gentrification or disinvestment, and in relationship to the city plans and policies that help facilitate that change.

In some cases, Bierbaum says that residents feel closures are “necessary” responses to dramatic demographic shifts, even if “draconian”; city officials are “doing the best they can to deal with things out of their control” in terms of fiscal management, she says. But in other cases, residents see closures as yet another manifestation of systemic oppression, closely related to other kinds of disinvestment within neighborhoods. “In this way, not only closures but also school building disposition is actually experienced as dispossession,” Bierbaum explains.

A majority of closed schools are converted into charter schools, with a second significant chunk repurposed into residential apartments. Other buildings are demolished or left vacant. Interviews with experts in several cities reveal that school district officials have not prioritized urban-planning questions, like those Bierbaum is asking, when deciding whether to close schools.

Clarice Berry, the president of the Chicago Principals and Administrators Association and member of a state legislative task force focused on Chicago school facilities, says the Chicago public school district was simply uninterested in discussing those sorts of civic topics. “At no time have they wanted to study that, or even been interested in discussing it,” she says. “The district spends all their time trying to keep us from getting data [on school closures] that could show us how they could make improvements.” While the task force has repeatedly asked the district to track kids who have been shuffled around from school to school, by and large Chicago and other urban districts have not carefully tracked how school closures have impacted students, families, and communities.

SHORTLY AFTER J4J BEGAN ORGANIZING, another network formed—the Alliance to Reclaim Our Schools (AROS)—comprising ten national organizations, including the American Federation of Teachers, the National Education Association, and J4J. Through weekly email newsletters and support for on-the-ground organizing, AROS has helped mobilize individuals looking to fight for public education. Parents and community groups hope they can agitate districts to think creatively about facility space, and invest more in neighborhood schools.

In mid-February, AROS helped stage the first-ever national day of “walk-ins,” where students, teachers, and parents at 900 schools in 30 cities across the country rallied in support of increased school funding, local schools with wraparound services, charter school accountability, and an end to harsh discipline policies, among other demands.

Their action built on momentum that’s been brewing over the past two years around the idea of “full-service community schools,” or schools that offer not only academics but also medical care, child care, job training, counseling, early college partnerships, and other types of social supports. This school model, which dates back more than a century, can be particularly beneficial for low-income residents who face challenges like accessing transportation.

In February, the Center for Popular Democracy released a report on the roughly 5,000 self-identified community schools across the country, lifting up particularly successful examples and offering strategies on how to replicate their success. One such school was Reagan High School, a poor and minority school in northeast Austin, Texas, which adopted a community schools strategy five years ago. In 2008, the local district was threatening to close Reagan due to its declining enrollment and its below–50 percent graduation rate. Parents, students, and teachers began organizing around a community schools plan to save Reagan from closure, and the district gave them permission to give it a shot. After expanding supportive services, like mobile health clinics and parenting classes, after changing its approach to discipline, and after expanding after-school activities, among other things, graduation rates at Reagan have now increased to 85 percent, enrollment has more than doubled, and a new Early College High School program has enabled many Reagan students to earn their associate’s degree before they graduate.

Implementing community schools can be difficult, particularly to the extent that it requires schools to adopt joint-use policies so that facility space can be shared with other public agencies and nonprofits, many of which have no prior experience working together. Some states and local districts have been much more amenable to these types of partnerships than others. “Yes, there’s complexity. But my response is ‘welcome to modern life.’ Stop whining, we know we can do this,” says Filardo of 21st Century School Fund.

Political support for full-service community schools is also on the rise.Philadelphia’s new mayor, Jim Kenney, has pledged to create 25 new community schools by the end of his first term. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio aims to create 200 community schools during his tenure. The new federal education bill passed in December even authorizes grant-funding for community schools, which has incentivized many other cities and states to begin thinking about how to take advantage of this opportunity.

I sat down with Antoinette Baskerville-Richardson, a member of Newark’s elected advisory school board, to learn more about her interest in expanding community schools. With more than one-third of Newark’s children living in poverty, Baskerville-Richardson says local leaders have been looking for ways to address the harms of poverty while also supporting student achievement and school success. After five years of controversial education reforms pushed by Republican governor Chris Christie and his appointed superintendent, Baskerville-Richardson says the Newark community is just plain tired.

“There was a period when all our efforts were basically just fighting against these reforms being imposed on our communities,” she explains. “At the same time, we realized that the conversation could not just be about what we were against, and we had to mobilize around what we were for.” And so, a little over two years ago, public school leaders and local advocates began to really home in on the idea of full-service community schools.

“We began to do a lot of research, we got in touch with experts, talked with people from the Center for Popular Democracy, the Children’s Aid Society, and people involved on the national level,” Baskerville-Richardson recalls. “We also started visiting community schools like in Paterson, New Jersey—which is also a state-controlled district—[and] in Orange, New Jersey, which has similar demographics as ours. We visited Baltimore, New York City; some of our people visited Cincinnati; we talked to people in Tulsa, Oklahoma. … We’re really looking to dig into a model that has been proven to work.” Starting in the fall of 2016, five full-service community schools are set to open up in Newark’s South Ward, its poorest area.

ON THE 60TH ANNIVERSARY OF Brown v. Board of Education in 2014, parents and community organizations in New Orleans, Chicago, and Newark filed federal complaints under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. They alleged that school closures in their cities have had a racially discriminatory impact on children and communities of color. The groups received legal assistance from the Advancement Project, a civil-rights organization.

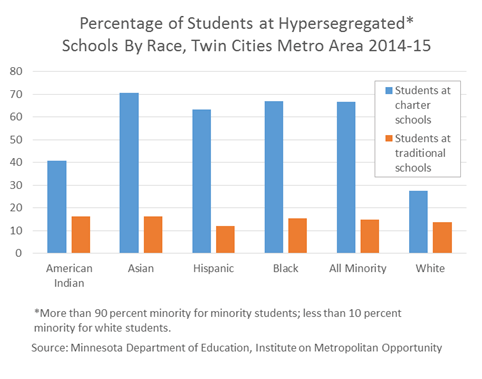

Jadine Johnson, an attorney with the Advancement Project, says they chose to file Title VI complaints because they wanted to raise disparate impact claims. “When districts are making these decisions they don’t say ‘we’ll close black and Latino schools.’ They’ll say ‘we’ll close schools that are under-enrolled or under-achieving,’” she says. “But those decisions can still have discriminatory effects on black and brown students.” In Newark, for example, during the 2012–2013 school year, white students were nearly 20 times less likely than black students to be affected by school closures, despite what would be predicted given their proportions of student enrollment.

Ariel Bierbaum says her field research demonstrated that many Philadelphians understood school closures as symbols of continued and consistent disrespect and disinvestment for poor communities of color. “Many of my interviewees tied school closures to urban renewal, to their parents’ experience, … [to] the Jim Crow south and migrating north,” a legacy that dates back to slavery, she says. “For them, these closures are not a ‘rational’ policy intervention to address a current fiscal crisis. School closures are situated in a much longer historical trajectory of discriminatory policymaking in the United States.”

J4J has also helped to bring a racial-justice lens to the school-closure conversation, namely by forcing the public to discuss it within the context of discrimination, segregation, underfunding, and marginalization—both inside and outside of schools. In some respects, there’s a seeming irony around efforts to save schools in poor and racially segregated neighborhoods—these are the same schools that were treated as expendable during the desegregation era. But residents understand that their schools aren’t closing for integration purposes, and if one looks closer, it is clear that aims to create more diverse neighborhood schools are still very much on the table.

In December, the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the Department of Education reached a groundbreaking resolution with Newark Public Schools to aid those who may have been negatively impacted by Newark’s closures. Johnson, the Advancement Project attorney, says she believes the Newark OCR resolution “sends a loud message” to school districts that may be considering similar types of school closures. “We see this [as] a multi-year strategy,” she explains. “This resolution is hopefully the first of many agreements, and the first step to sounding the alarm for why public schools should remain public.”

Meeting with some parent activists who helped to file the Newark Title VI complaint, I wanted to see how they were feeling about the OCR resolution. Sharon Smith, the founder of Parents Unified for Local School Education (PULSENJ), thinks that irrespective of whatever remedies their superintendent proposes, it will take generations until Newark’s South Ward heals.

“It’s always very scary to me when people who are guilty of something, like the district is, say ‘Yes, we are guilty, but we’re going to fix this our own way without the input of the people who were hurt,’” says Darren Martin, another parent involved with PULSENJ. “We’re happy the OCR took our complaint seriously, but it feels almost like the police are policing themselves. How do you allow the person who helped design all these destructive policies [to] also design the remedy?”

IN FEBRUARY, I VISITED KELLY HIGH SCHOOL, a full-service community school on the southwest side of Chicago, serving a student body that’s more than 90 percent low-income. Kelly used to draw a large Italian, Polish, and Lithuanian population, but now predominately serves Hispanic students. With the help of the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, a local community organization, Kelly offers all sorts of programs for parents and children, ranging from tax-prep classes and English-language instruction, to tutoring and political organizing. The academic improvement Kelly students have shown over the past decade has also been substantial—targeted interventions have helped more at-risk students stay on track to graduate, and the school is now ranked as a Level 2+ in the district’s rating system—where the highest possible score is a 1+ and the lowest is a 3.

But Kelly’s progress, both academically and as a civic institution, is threatened by increasing budget cuts, declining student enrollment, and the growth of charter schools in the surrounding area. In July 2015, the Noble Network of Charter Schools, the largest charter chain in Chicago, submitted a proposal to open a new high school a few blocks away from Kelly. Students, parents, and teachers began mobilizing against the proposal, concerned that this new project would siphon even more resources from their already-pinched school, which had been forced to slash programs and teaching positions over the last few years. In October, 1,000 Kelly High School students walked out of class to protest the proposed new school. Yet despite overwhelming local opposition, the unelected Chicago Board of Education voted unanimously to open the new charter.

It’s possible that over the next few years, Kelly High School’s fiscal strain will become just too much to manage, and the school will be slated for closure, too. “The narrative to close schools is essentially a budget one, which can be extremely powerful,” says Filardo. Even if the budget savings turn out to be fairly small, or nonexistent.

One way to reduce budgetary pressures on schools, thereby helping prevent school closures, would be for states and the federal government to pay more, particularly toward local capital budgets. Decades of social-science research have shown how unsafe and inadequate school facilities can negatively affect students’ academic performance—particularly when a school has poor temperature control, poor indoor air quality, and poor lighting. Researchers also find that the higher the percentage of low-income students in a district, the less money a district spends on the capital investments needed to keep school facilities in good repair. The most disadvantaged students tend to receive about half the funding for school buildings as their wealthier peers. And often, low-wealth districts spend more from their operating budgets on facilities—paying for large utility bills, more demanding maintenance for old systems, and the high costs of emergency repairs. It’s not a coincidence that affluent communities invest more in their public school buildings. “They improve and enhance their school facilities because it matters to the quality of education, to the strength of their community, and the achievement and well-being of their children and teachers,” says Filardo.

In other words, increasing state and federal spending could both help struggling urban schools, and also help fortify communities more broadly. Filardo thinks districts should be able to leverage up to 10 percent of their Title I funds to help pay for capital expenses—right now, Title I funds can only go toward local operating spending. Or, even better, Filardo thinks the federal government should start contributing at least 10 percent toward district capital budgets, just as it contributes 10 percent to district operating budgets.

“Schools belong to the entire community, and it should be the state and federal government’s job to find the right policy levers so that we can really advance our educational and economic development together in the best, most equitable way,” she says.

Battles about how best to save and improve public education are sure to intensify in the coming months and years. No researcher has been able to conclusively say what the optimal policy intervention is for students in terms of boosting academic achievement. And some individuals are certainly more sympathetic to closing schools, particularly if it means their children could attend higher-performing district schools or charters. Even on the question of school governance, researchers have reached no clear consensus on whether state takeovers or local control is better for student outcomes or fiscal management. Nevertheless, there’s consensus that any system which generates uncertainty and distrust is a recipe for disaster.

Reflecting on the past four years in her city, Lauren Wells, the chief education officer for Newark Public Schools, notes that reform-minded leaders expanded charter schools quickly without really taking into account the impact such decisions would have on existing schools. A recent report from the Education Law Center, a legal advocacy group, found that the combination of the state’s refusal to adequately fund New Jersey’s school aid formula, coupled with rapid charter-school growth, has placed tremendous strain on district finances, forcing Newark to make significant cuts to district programming and staff. “We really want to move the conversation away from charters versus district schools,” Wells says. “We’re trying instead to build a coalition around this idea that we are the guardians of all children. That should be the basis of any decision that we make.”